Why the damage from extreme weather is a profit center, and not a risk for insurers.

Here is a climate finance riddle. Why are insurance companies posting record profits even as climate-related losses from natural disasters reach historic highs?

Despite a $182 billion price tag for losses due to weather-related disasters in the US last year, property and casualty insurers reported a near-doubling of their earnings over 2023. After-tax profits of the industry totaled $171 billion last year, compared to $92 billion the previous year. Last year was also an especially good one for home insurers, who booked the first aggregate underwriting profit on home insurance since 2019.

The reinsurance industry is also doing more than just fine, reports Peter McKillop, founder and CEO of Climate & Capital Media. The world’s biggest reinsurers — Munich Re, Swiss Re, Hannover Re, and SCOR — collectively reported a record $13 billion in earnings last year, according to Moody’s. “Climate disaster is good business for banks and insurers,” he concludes.

Wait! I Thought the Climate was Bad for Insurers

The answer to this apparent contradiction is simple, as millions of Americans are now discovering. Cash-flush insurers like State Farm are raising premiums faster than claims are rising, while reducing their exposure in high-risk areas.

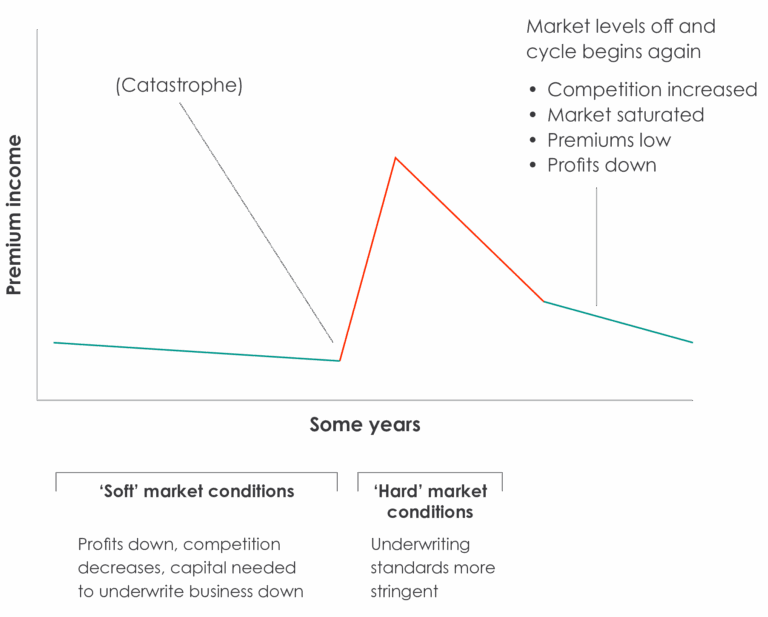

In other words, your loss is their gain. In the industry, it is referred to as the “insurance cycle.” The insurance cycle is a phenomenon that has been understood since at least the 1920s. But now rising climate-related property damage is exacerbating the cycle. American premium holders are now experiencing the portion of the cycle when insurers tighten their underwriting standards and sharply raise premiums after a period of growing underwriting losses.

The “Insurance Cycle”

During a hypothetical “soft” period in the cycle (see above), premiums are low, the capital base is high, and competition is high. Premiums continue to fall as insurers take greater risks to compete or risk losing business in the long term.

Then, catastrophe strikes, such as this year’s firestorms in Los Angeles. At this point, the market hardens, as premiums soar and underwriters either reduce risk or pull out altogether, as many insurers have done in high climate risk states like Florida, Louisiana, and California.

In California, companies are protecting their bottom lines by simply pulling coverage, as they assess the $40 billion cost of wildfires earlier this year. As competition shrinks, rates rise, and profitability returns. This occurred after Hurricane Katrina devastated a swath of the US Gulf Coast in 2005, when riskier, less well-capitalized insurers filled the void left by departing insurers. The Insurance cycle starts again.